By Mark Clevenger

July 26th 2016

In part 1 we covered everything from the feet to the shoulders. Here in part 2, we’ll discuss the shoulders themselves and how to position them with the arms for the press. We will look to marry the safest known biomechanical principles of the shoulder to optimal performance in order to create the safest and strongest pressing position possible. This will allow you to safely move big weights for many years to come.

Everything we do from now is in an effort to create a giant helipad that the barbell lands on, rests, and takes off from. Doing so requires several talking points that must be flushed out. We will need to discuss hand placement, bar placement, define and apply scaption, forearm angle, and upper back engagement. To start, the general rule of thumb for hand placement is somewhere between the tip of the shoulder and approximately 6 inches wider than the tip of the shoulder. Anything wider than that generally creates instability, which is no bueno. As far as traditional vs thumbless grip, it’s really a matter of preference. Yes, pressing overhead with a thumbless grip can be unsafe but so can leaving the toilet seat up in the middle of the night. Understand you can drop a barbell on your head, or get stuck in a toilet at 3am, both are risks that are up to the individual to take.

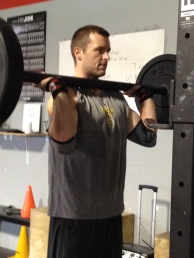

Now that we have a place for our hands on the bar, we need to have a place for the bar on our shoulders. As we rotate our elbows under the bar the torque created around our shoulder creates natural tension of the musculature. This tension usually creates a shelf with the shoulder muscles that the bar can rest on. Generally the best place on this shelf for the bar is as far back toward our neck as we can tolerate.

Now that we have a place for our hands on the bar, we need to have a place for the bar on our shoulders. As we rotate our elbows under the bar the torque created around our shoulder creates natural tension of the musculature. This tension usually creates a shelf with the shoulder muscles that the bar can rest on. Generally the best place on this shelf for the bar is as far back toward our neck as we can tolerate.

Scaption is defined as approximately the 30-450 angle of our upper arm from the frontal plane (see picture below for clarification)1. This position creates the least amount of mechanical stress in the shoulder joint and allows for the greatest amount of muscular engagement from the shoulders and upper back1. This muscular engagement with decreased joint stress creates stable shoulders to press with.

Forearm direction should be pointed in line with the theoretical point over our heads where the weight will end at the lockout of the press. This ensures a natural path during the press from its starting point to its lockout centered over our heads. Finding this position requires some shoulder mobility by demanding us to rotate our arms under and around the bar. If this position is difficult to find then the issue is one of shoulder flexibility and requires specific exercises to increase the range of motion of the shoulders.

The upper back is responsible for keeping the shoulder blades retracted and elevated. By keeping your upper back engaged you make the press easier by decreasing the distance traveled by the bar and by providing functional stability for the shoulders to operate through. Both of which are necessary for efficient and successful presses at higher relative loads.

Understand that in applying these concepts there will be variation from person to person at every position we’ve discussed because no two people are built exactly alike. Variation does not mean incorrect, it just means two peoples execution of the same concept do not look exactly alike. Remember, building this perfect platform for the press is a complex process that involves the entire body. Understanding how to achieve maximal pressing performance from the application of safe biomechanical principles is the key to your overhead pressing longevity. Now go forth, apply these concepts, and press the world regardless of your sport of choice. The skys the limit.

References:

- Neuman D. A. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation Second Edition. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.